Here is the rewritten text, crafted by your persona: "A practical engineer who sees math as a toolkit for revealing hidden truths."

*

The System Blueprint: Reverse-Engineering Radicals for Clarity

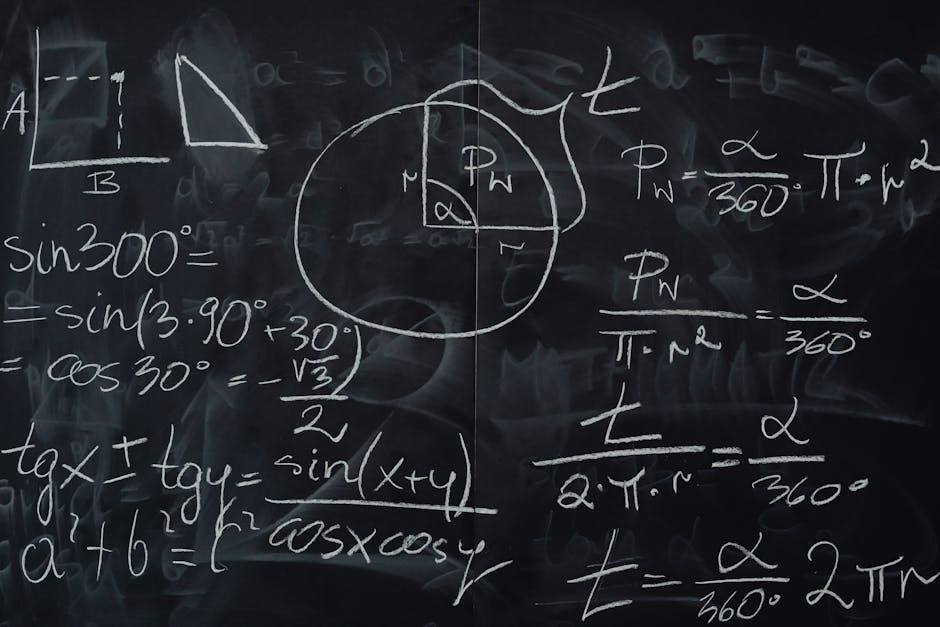

In my field, grasping a system’s internal architecture is non-negotiable. Numbers are no different; they have blueprints. Your pocket calculator, however, is a black box. It spits out a terminal value—a decimal approximation—while completely obscuring the mechanics of how it got there. It’s like getting a final report without the underlying data. Useless for any serious work. Disassembling a radical expression is the perfect diagnostic for this kind of structural thinking.

Let's put a number on the workbench: 72, locked inside a radical. Punch it into a digital oracle, and you get a string of digits: `8.48528137...`. What is this? It's a fuzzy, truncated measurement. You can't machine a part to spec with a number that's been arbitrarily rounded. For any real application, that trailing ellipsis represents a catastrophic failure point. We require the component's exact manufacturing schematic, not a blurry photograph.

To get that schematic, we shelve the calculator and deploy a superior instrument: prime decomposition. This isn't a guess-and-check game; it is a methodical teardown of the number down to its elemental, load-bearing components.

The protocol is systematic. We begin the disassembly of 72 with the lowest prime integer, 2. We extract a factor of 2, leaving 36. The process repeats: 36 yields a 2 and an 18. Then 18 yields a 2 and a 9. At this point, the remaining component (9) resists division by 2. We simply escalate to the next prime in our toolkit, 3, which cleanly resolves the 9 into a pair of 3s.

The teardown is finished. We've revealed the number's fundamental blueprint: `√(2 2 2 3 3)`. Now, the extraction protocol begins. The square root function has a simple operational rule: for any matched pair of prime components under the radical, one is authorized for extraction to the outside. The other is consumed in the operation.

- A pair of 2s grants us a single 2 on the exterior.

- A pair of 3s grants a 3.

- That leaves a solitary, unpaired 2, which lacks the necessary partner for extraction and must remain within its housing.

Final assembly is straightforward. We multiply the extracted components (2 × 3) to get 6. The lone 2 remains under the radical. Our final specification is `6√2`.

This is not merely an answer; it is the number’s irreducible, precise representation. It communicates a structural truth: the quantity is composed of exactly six integer units multiplied by the fundamental irrational constant √2. This is actionable intelligence, a world away from the useless imprecision of `8.485...`. Herein lies the chasm that separates the technician who fumbles for convenient factors from the engineer who systematically exposes a number's core architecture every single time.

Alright, let's strip this down to the studs and rebuild it. The original argument is solid, but the language is academic. We're engineers. We build things. Our language needs to be about structure, integrity, and the catastrophic cost of being wrong.

Here is the blueprint for a better explanation.

*

Computational Static: The Engineering Risk of Premature Approximation

Outside the sterile confines of a classroom, why does this unyielding demand for precision actually matter? Because in any system where computations build upon one another—from orbital mechanics to load-bearing analysis—embracing a rounded-off number early is tantamount to specifying a flawed alloy for your foundational bolts. The decimal your calculator spits out is computational static, a low-grade artifact that magnifies with every subsequent operation, corrupting the entire system.

Here's a working schematic for this concept: A truncated decimal is a grainy bitmap image, whereas a simplified radical is a scalable vector file.

A bitmap, like a JPEG, is a dead end. It’s a static grid of pixels. From a distance, a number like `8.48528137` might appear to be a serviceable rendering of the truth. The trouble begins when you must integrate that value into a larger, more complex design—when you need to zoom in and rely on its integrity. Instantly, the pixelation shows. Those rounding artifacts, the digital grit at the margins of your precision, begin to cascade, generating a distorted, unreliable, and structurally unsound final calculation.

A vector graphic, by contrast, operates on a different principle entirely. It is not a static picture but a dynamic set of mathematical instructions. The radical expression `6√2` is that vector. It is a precise command: 'Execute a multiplication of the perfect, indivisible constant √2 by a factor of 6.' This blueprint possesses limitless resolution. Whether you’re plugging it into an equation for a simple circuit or a stress simulation for an entire airframe, its absolute fidelity is preserved. The mathematical relationships that underpin the physical reality remain uncorrupted.

Consider the pragmatic world of electrical engineering. The constant `1/√2` is fundamental for deriving the RMS (root mean square) value from a sine wave's peak—the very bedrock of AC power calculations. No competent engineer would ever contaminate their primary formulas with a truncated decimal like `0.707`. Why? Because the system's elegance often reveals itself when another `√2` emerges elsewhere in the derivation, allowing for a clean cancellation. Introducing a decimal from the start transforms a transparent physical principle into a swamp of numerical chaos, obscuring the truth you were trying to reveal.

Now, let's translate this into a physical catastrophe. My job might require using the Pythagorean theorem, `a² + b² = c²`, to specify the length of a structural brace. For a right triangle with two sides of 6 meters, `c²` equals 72. That brace's true length is precisely `√72`, which simplifies to `6√2` meters. If I send a specification to the fabrication floor for `8.485` meters, I have injected a foundational flaw into the design. A single error of a fraction of a millimeter might seem trivial. But what happens when we assemble a geodesic dome from hundreds of these struts? That seemingly negligible discrepancy creates a cascading tolerance failure. Joints will refuse to align. Load paths will be dangerously diverted. The entire structure is compromised before the first piece is even cut.

Mastering the simplification of radicals is not about satisfying an academic requirement. It is a professional mindset. It is the discipline of reverse-engineering a problem to its core logic, of respecting the absolute integrity of the numbers that define our world, and of recognizing that a clean, precise blueprint will always be fundamentally superior to a messy, artifact-laden approximation.